Trobriand Bundles of Sorrow

Photographs by Johanna Rains, text by Allan Darrah

It was baskets of bundles such as these that influenced Annette Weiner to change her course of study, thereby leading her into making a major contribution to the Trobriand ethnographic literature.

These beautifully subtle patterns contain common Massim motifs.

Ever since 1978 when Annette Weiner published Women of Value, Men of Renown, students have focused on women's mortuary exchanges involving gifts of thousands of banana leaf bundles, a subject unreported by the legendary Malinowski.

On her arrival Weiner, who had set out to study the male realm of carving, became enthralled with women's exchanges of these bundles of sorrow, which were given by women who were close matrilineal kin of the deceased to his or her principal affines in payment for their onerous services in mourning the deceased. She discovered women's wealth and teased out the processes by which women's wealth impacted the affairs of men. As it turns out, men are obligated -- in part by the annual gifts of yams from their wives' brothers -- to use their own wealth to secure bundles and grass skirts for their wives to compete in giving bundles and receiving status in proportions to the relative amount given away.

Although Weiner wrote extensively about bundles, there are over 700 references to them in her works; she reports their ubiquitousness in everyday life as well as mortuary exchanges, but provides us with very little information about their manufacture nor does she tell us much of their symbolic import, (See Note 1)

The photographs that follow show the process of imparting designs to bundles and give rise to speculations about these unanswered questions.

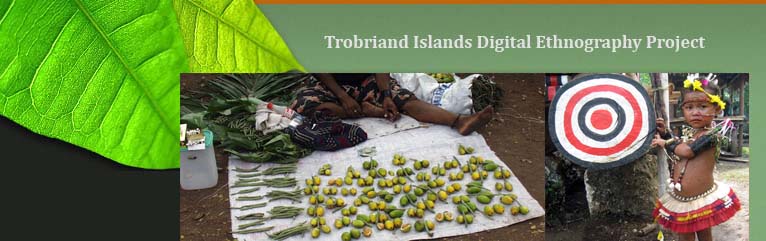

The manufacture of the bundles begins with a green banana leaf, which is cut up into sections. Women plant and own a family's banana trees while men own most of the other produce.

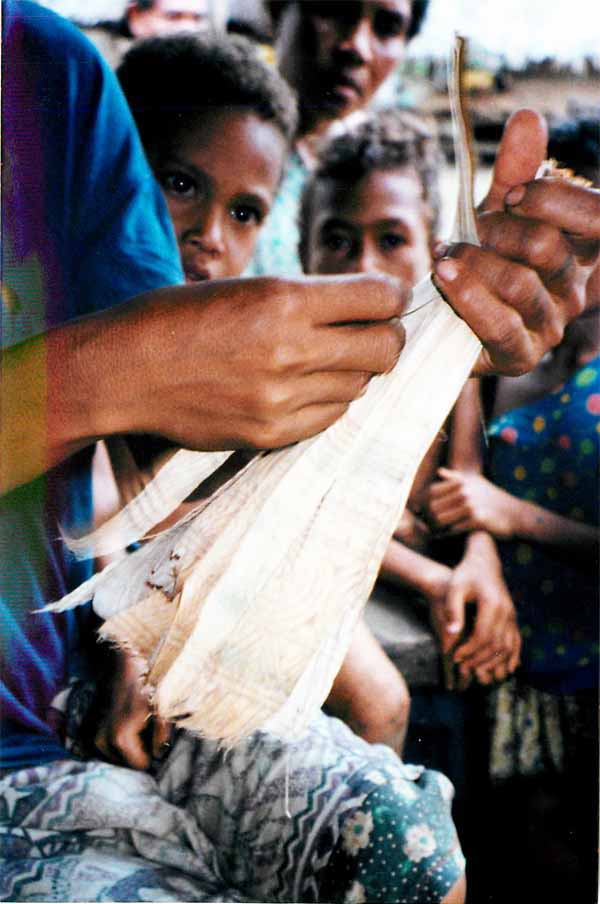

The pieces of leaves are then scrapped on a board to remove the dark green pulpy leaf covering and expose the lighter fibrous interior. The board has a pattern cared into it and when the scrapper passes over the incised portions the flexible leaf gives way so that the exterior adjacent to the depressions is not removed, leaving a dark, contrasting design on the lighter, scrapped background. The process of scraping designs into banana leaves is called tagini. (See Note 2)

Rains found that men carve these boards for their wives or sisters. They are a relatively new innovation that started within living memory. Before their inception women would incise designs on the leaves by hand.

The scrapped leaves are then bleached in the sun until dry, but into strips and then collected into a bundle, the end tied. The Trobriand term for a bundle is nuninga. Weiner observes that: "The term nunu means 'breast, nipple, mother's milk.'" It is a term of endearment used after a mother's death. As a verb, nunu means "to suck." Nunu also means "same dala." The suffix of nununiga is possibly from the word naga, "to share." The duplicate form of naga, to emphasize the sharing, is niganga." (Woman of Value, p.92) Trobrianders indirectly compare the process of a father's nurturing an infant with the mortuary duties of affines handling a corpse. (See Note 3)

If bundles are symbolic of the nurturing powers of breasts there is a significant difference: bundles are whitened by exposure to the sun while parturients are whitened by its avoidance. (See Note 4)

The fibers of a fraction of the thousands of bundles made each year are dyed and used to make the women's skirts.

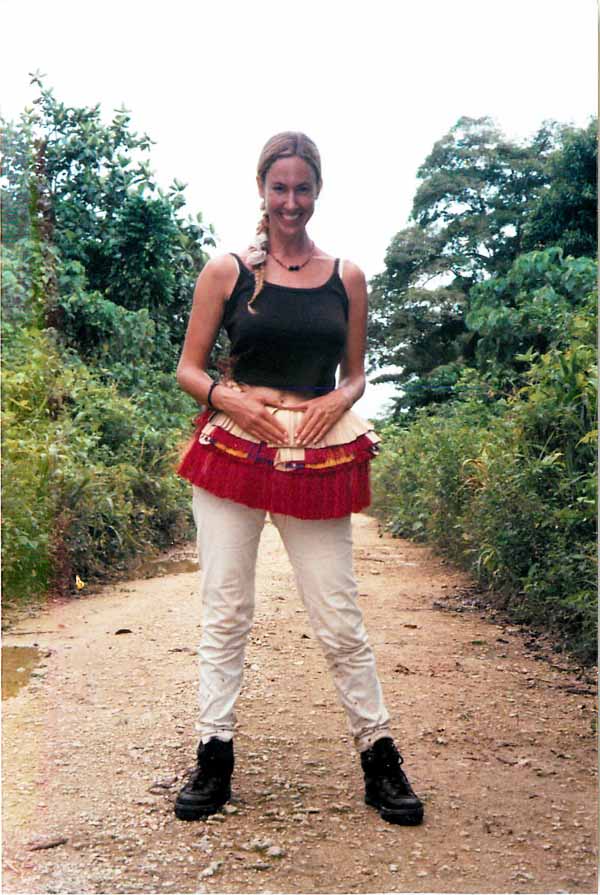

Red is the color of desire and seduction. Young women wear short red skirts until they are married, when their husband's sisters give her a more modest, longer white skirt appropriate to new monogamous status. When her husband dies a woman is not only sequestered, her head is shaven and she wears a dark skirt. She is liberated from her mourning and paid for her services by the husband's sisters, who give her a large number of red skirts. Skirts are clearly the major idiom of women's life passages. They are created by symbolic breasts transformed, darkened through the multiple exchanges which cleanse women of the pollution of death and restore rends in the fabric of society.

Clearly these are bundles of both sorrow and joy.

Johanna Rains wears the skirt of adolescence.

Notes

1. One of the things to be observed in her Disappearing World film, but of which she only gies passing reference, is that the leaves that make up the bundles have a design imparted onto them. In this film we learn that Trobrianders with more western lifestyles have to substitute gifts of cloth for bundles and skirts. Many fascinating questions await answers. Are these lines a modern innovation to make these traditional items of exchange more like the cloth that is being substituted? Is there any significance imparted to these lines except to make the bundles more attractive? Some bundles have a name imcorporated into the designs. Does this name identify the person who made the bundle or the person who is being mourned? Are there any traditions associated with the patterns of the design and is there any standardized lore about the meanings of these designs? (Note triggered by clicking on the DEPTH icon)

2. Although some scholars, including Malinowski, are of the opinion that traditional Trobriand-carved designs were purely decorative, there are others who argue that their otifs, carved and incised, also contained representations as well as hidden meanings. Austen states that canoes, lime sticks, betel-nut pestles, mortars, yam boars, and house boards were never considered complete unless special markings were incised in the wood. He goes on to report that these markings, called ginigini, were in fact of magical significance as well as of aesthetic value. Perhaps the incising of meaning into Trobriand carvings is something akin to hieroglyphics, i.e. representative symbols, which when combined form a much larger pattern of meaning. Ginigini is to carve. Gini is the decorate or draw. Thus skirts, which are made from the fibers of old bundles incorporate their on ginigini and Malinowski reports that some women own magic the making of skirts.

3. Weiner has remarked on the similarities and differences in the idioms of the alpha and omega life transformations.

The restrictions for new mothers are similar to the prohibitions that a Trobriand widow or widower must observe. For example, separated from all but the most minimal social interaction, such women each sit on a high bed at the back of the room. Nursing mothers, like mourners, also must give up eating yam and pork, the two most favored foods. There are differences as well -- for the parturient a low fire burns under the bed, whereas for mourners there is no fire. Mourners blacken their bodies in an attempt to cover their own social identity. A woman who has given birth also covers her body, but with a light banana-leaf cape that gives the effect of lightening the color of the body. The similarities of seclusion for birth and mourning, with their important oppositions between warmth and cold and light and dark, suggest that death and birth, although decidedly opposite states of being, nevertheless are linked together in a more deeply meaningful way. (Women of Value, p. 53)

4. To paraphrase Freud's famous phrase on the search for meaning "When is a cigar more than just a cigar?" Could it be that the symbolism of bundles lies in part in the quotidian details of their manufacture? The leaf's dark exterior is removed to expose a white interior. This is the very transformation, which takes place in Tuma when a baloma sheds its darkened, aged skin to be reborn white and young again. The spring whose waters accomplish this feat of rejuvenation is called supiwina, which Malinowski translate was "washing waters." Supi is the term for the process, in the garden cycle, of setting fire to mounds of vegetable debris, collected by women, to prepare the garden for planting. Baldwin indicates that supi means to singe. Supwana is to go under or beneath while supusopu is to plant yams. Wina, according to Malinowski, is an archaic form of wila, which means cunnus. A possible gloss of supiwina is singed or blackened genitals. If, as Brindley suggests, the rites of garden magic are homologous to the human life cycle, then the supi/burning of the garden mounds, in order to prepare mother earth for planting, appears to be analogous to rejuvenation of the baloma as the spring called supiwina. The supi burning turns the earth/cunnus black. Black and white are key indicators of the health of both humans and yams. There is an emphasis on white tubers being good and healthy, while black ones are bad or diseased. At the basi thinning the black tubors are removed and white ones left behind to mature. At harvest tubers are black. Humans follow a similar chromatic development patterns. They are born white aided by rituals to ensure this outcome, and like coconuts darken with age as the effects of magic and sorcery appear on them. After a death occurs the women of the deceased's dala are busy creating pseudo breasts, symbols of youthful whiteness, and vitality by a process which peels away the dark surface to reveal a white interior.